Given that half of the world’s population is female, it is nothing less than disappointing and dismaying that there are very few women in positions of power, in legislatures and at decision-making tables. Apart from a few handful of states, most of the world’s legislatures do not even descriptively exhibit the gender balance of their respective electorates. Add the element of race and ethnicity – and the picture becomes even bleaker. However, these problems are not inevitable; policies such as quota systems can be enacted to allow women to fully politically engage, especially those from a minority ethnic background, as argued by the Fawcett Society.

As of January 2019, only 21 countries have women as either their heads of government or as heads of state. To illustrate the scale of the problem, that’s 21 states out of the 193 officially recognised independent states by the United Nations; in terms of statistics, that’s 10.8% of states.

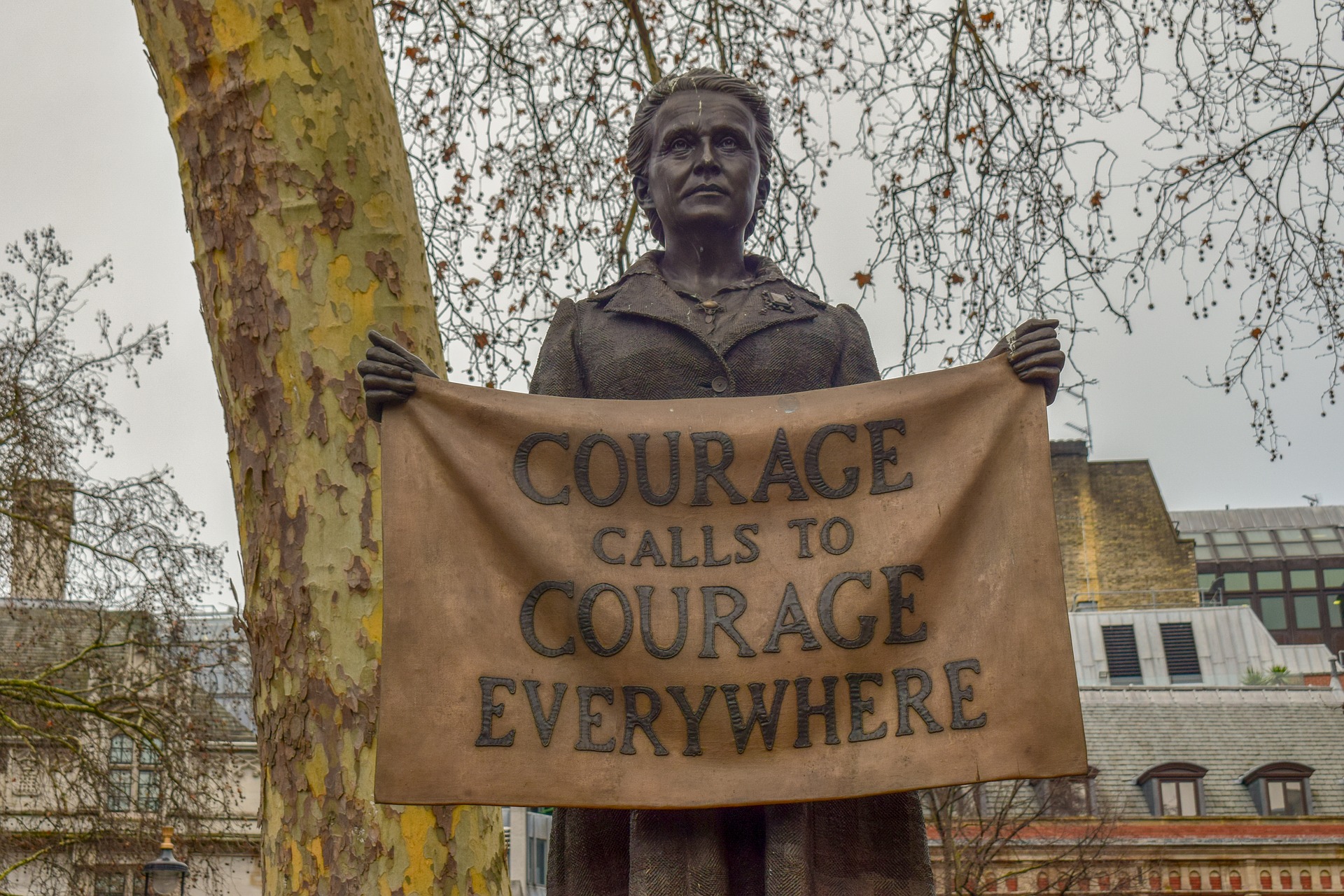

The descriptive under-engagement and under-representation of women is also part and parcel of British politics. Currently, women only constitute a dismal 26% of cabinet ministers and 32% of Members of Parliament in the in the lower house of Westminster Parliament. These statistics are even more appalling because gender imbalance is taking place in the chamber that is hailed as the inventor of a parliamentary democracy. Additionally, even more painful is the fact that these statistics represent the state of affairs 100 years on since some women were granted the right to vote. To be clear, the current level of political engagement is the outcome of 100 years’ worth of struggle.

As a matter of clarification, there isn’t a gender imbalance just in political engagement, but in legal, leadership and media roles as well (Toppings, 2018). In other words, gender imbalance is a society-wide issue.

The aforementioned statistics, despite recent improvements, are as dreadful as they are by themselves. These statistics become even more dreadful when one looks at this matter through the lens of intersectionality. The concept of intersectionality refers to the act of looking at a pattern of inequality through overlapping social characteristics.

To elaborate, one can look at the level of political engagement based on gender imbalance and go beyond that by looking at how race creates a further inequality within the gender imbalance. For example, the General Election in 2017 returned 208 women to the House of Commons, of whom only 26 are from an minority ethnic background. These 26 women represent four per cent of the House of Commons, as illustrated in Figure 1 below. Using an intersectional perspective therefore suggests that some people confront double barriers with regards to political engagement: gender and race. History suggests that this double barrier is nothing new as black and Asian women who fought for a vote had been side lined from the spotlight a century ago.

At present it would not be an exaggeration to describe the members of the House of Commons as male, pale and stale because of the statistics outlined in the above paragraphs. But, there is light at the other end of the tunnel; the present situation can be improved. That particular improvement requires a systematic approach of introducing quota system.

Quotas based on gender and race is an incredibly controversial proposition – and is vehemently opposed by some sections of society. By way of explanation, it is claimed that quotas violate principles of meritocracy and therefore foster an uneven playing field by giving women, especially ethnic minority women an advantage over Caucasian males.

This argument is false because it is based on a flawed premise. It is because meritocracy is a myth that quotas must be enacted to create a level playing . To elaborate, the status quo is not meritocratic because it favours Caucasian males at the expense of everyone else. More importantly than this ideological and theoretical schism is the fact that quotas actually work, albeit to a certain extent . While quotas still maintain ‘majority men’s dominance of national legislatures’, it nonetheless produces diverse outcomes in those legislatures in terms of gender and ethnicity (see Hughes, 2011:604 for further information). If quotas can make women somewhat more politically engaged in states around the world, then why not in Britain?

Given the lethargically slow speed at which representation is improving, do you also think it is time to introduce quotas?

____________________________________________________________________________

Muhammed Raza Hussain is an award-winning writer: the Extra-Mile winner of the News Quest Young Reporter Scheme 2014 and received a ‘Talent for Writing’ certificate by Young Writers. Twitter @MuhammedRaza786 | Instagram: @M.Raza.H_