When Theresa May stated that she would stand down as Prime Minister on June 7th, the race for leadership of the Conservative Party – and indeed the country – was set in motion. Eleven candidates have already declared their intention to stand in the upcoming contest, with many more mulling over the decision. Whilst Brexit is likely to dominate the campaign, and rightly so, an underlying domestic crisis continues, that perhaps poses more long-term significance than our relationship with the European Union.

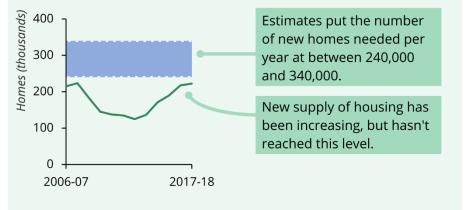

In December 2018, a government report into tackling the under-supply of housing in the UK, estimated that between 240,000 and 340,000 new homes need to be built for the UK to fully deal with the ongoing housing crisis. To put into perspective how far off the UK is in achieving these goals, in 2017/18 “the total housing stock in England increased by around 222,000 homes”, some way off the number required to address the issue (as illustrated in Figure 1 below).

If the Conservative Party is to remain in government beyond the next general election in 2022, dealing with the issue of housing will be perhaps the most pressing challenge to confront. Indeed, some of the potential leadership candidates have already outlined their proposals for solving the problem. Writing in The Mail on Sunday this past week, Dominic Raab outlined his somewhat ambitious targets for housing. The former Brexit Secretary wrote, “we must radically upgrade our ambition for building the homes young people and those on lower incomes can afford”. Despite seeming to offer a way out of the crisis, the UK will not fully be able to meet its housing targets unless we radically reform current laws and build on the green belt.

For many in the UK, the debate around relaxing planning laws and infringing on the sanctity of the green belt is a contentious issue. Indeed, when the concept of the green belt was first established in the mid-1930s it was done so with a noble intention of preventing mass expansion and controlling urban growth, whilst allowing individuals to enjoy the many benefits of the countryside and supporting a strong agricultural industry.

However, fast forward to 2019 and the green belt is no longer the idyllic, picturesque landscape that it was almost a century ago. Whilst the green belt covers approximately 13% of the total area in England, 16% in Northern Ireland and 2% in Scotland, a large proportion of it is no longer used for agricultural purposes. Instead of preserving the natural beauty of the British countryside, the outdated green belt policy now serves to protect a number of former industrial, run down and derelict sites-many of which could be built on to tackle the housing crisis.

Crucially, it is estimated that only 59% of London’s green belt is agricultural land, which provides a significant amount of room for development on land that currently serves little purpose. Research conducted by the Adam Smith Institute outlines the extent of the problem. In comparison with our European neighbours, “only two members of the EU 27 have less built environment per capita than the UK”. With roughly 90% of land in the UK remaining undeveloped, the neoliberal think tank suggests that just 0.5% of this land would need to be developed on to achieve to UKs housing targets for the next decade. If the next leader of the Conservative Party intends to take the housing crisis seriously, then relaxing the current planning restrictions around the green belt would be a notable first step.

Critics of increased development on the green belt will draw attention to the need to regenerate brownfield and inner-city sites instead. However, this is far more problematic than outward expansion. Brownfield sites within cities are simply, more often than not, unsuitable to build on. Whether it’s due to former contamination from industrial sites, lack of accessibility or limited transport links, just because there might be the availability of brownfield sites to build on, doesn’t necessarily deem it to be the best course of action. Additionally, the very implementation of the green belt limits the availability of land which can be developed on, subsequently putting upward pressure on housing prices and rent costs. For example, between 1955 and 2002, real house prices in the UK rose by almost 350%, presenting a significant obstacle to younger generations and those on low incomes, who strive to afford their own home.

If the Conservatives are to appeal to younger voters in forthcoming elections, they need to provide them with the opportunity of once again owning their own home. In 1980, when Margaret Thatcher introduced arguably her most successful domestic policy, the Right to Buy Scheme, she presented young people with genuine hope of home ownership. Building on the green belt will go a significant way to solving the housing crisis in the UK and if the Tories remain the party of individual opportunity and aspiration, the next leader must aggressively pursue this agenda and embark on a housing revolution.

_____________________________________________________________________________

James Plumb is a neoliberal commentator and Conservative Party member, who has written for numerous online publications, including the award-winning current affairs website Backbench UK. Twitter: @JamesRPlumb